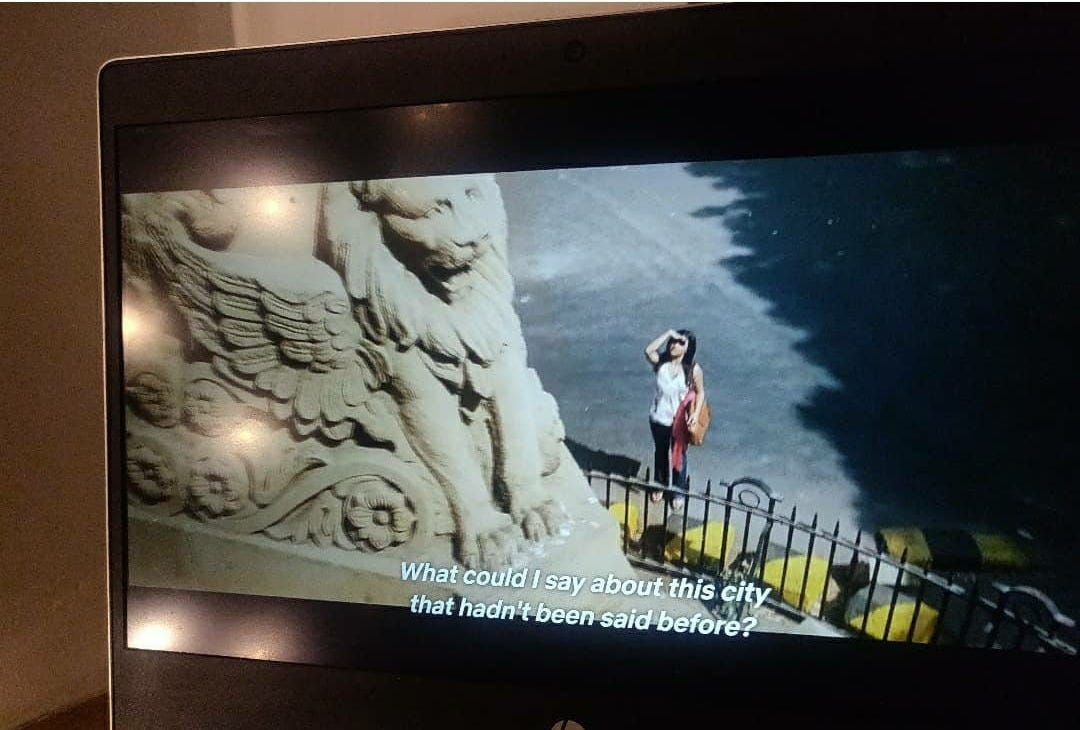

‘What could I say about this city that hadn’t been said before?’ Aisha Bannerjee wonders in Wake Up Sid, and as I begin my life in Mumbai, I have the same question. There is no truth that I have discovered yet, nor does my meagre experience contain anecdotes that neatly wrap in a story. I am new, I can only learn and I try to do just that.

I try learning by dipping my feet slowly into the salty waters of the Arabian Sea, feeling the chill, gauging the depth, hearing the splashes echo in the vacant voids of my life. I visit Mumbai two years before I decide to make it my own, to see if my romantic ideas of the city have any semblance to reality. I pay my tributes to the entire tourist checklist—Gateway, Mannat, Marine Drive, Prithvi and Candies. In truth, it is a farce. My mind is already made up, I have already fallen for the idea of the city and my romantic lens only grows crimson by the day.

I visit again, four months before shifting, to see how it feels to live in the city. This time I focus on a checklist of activities—jogging early morning through the streets of Fort, bargaining to my might at Colaba Causeway, sitting at Marine Drive after a rough workday, watching the sun dissolve into the sea, the sky pink and the lights from Malabar Hill towers adorning the horizon. I should be ready to take the plunge, yet something is missing. I don’t know how to swim.

The best way to learn how to swim, I imagine, is to read about it.

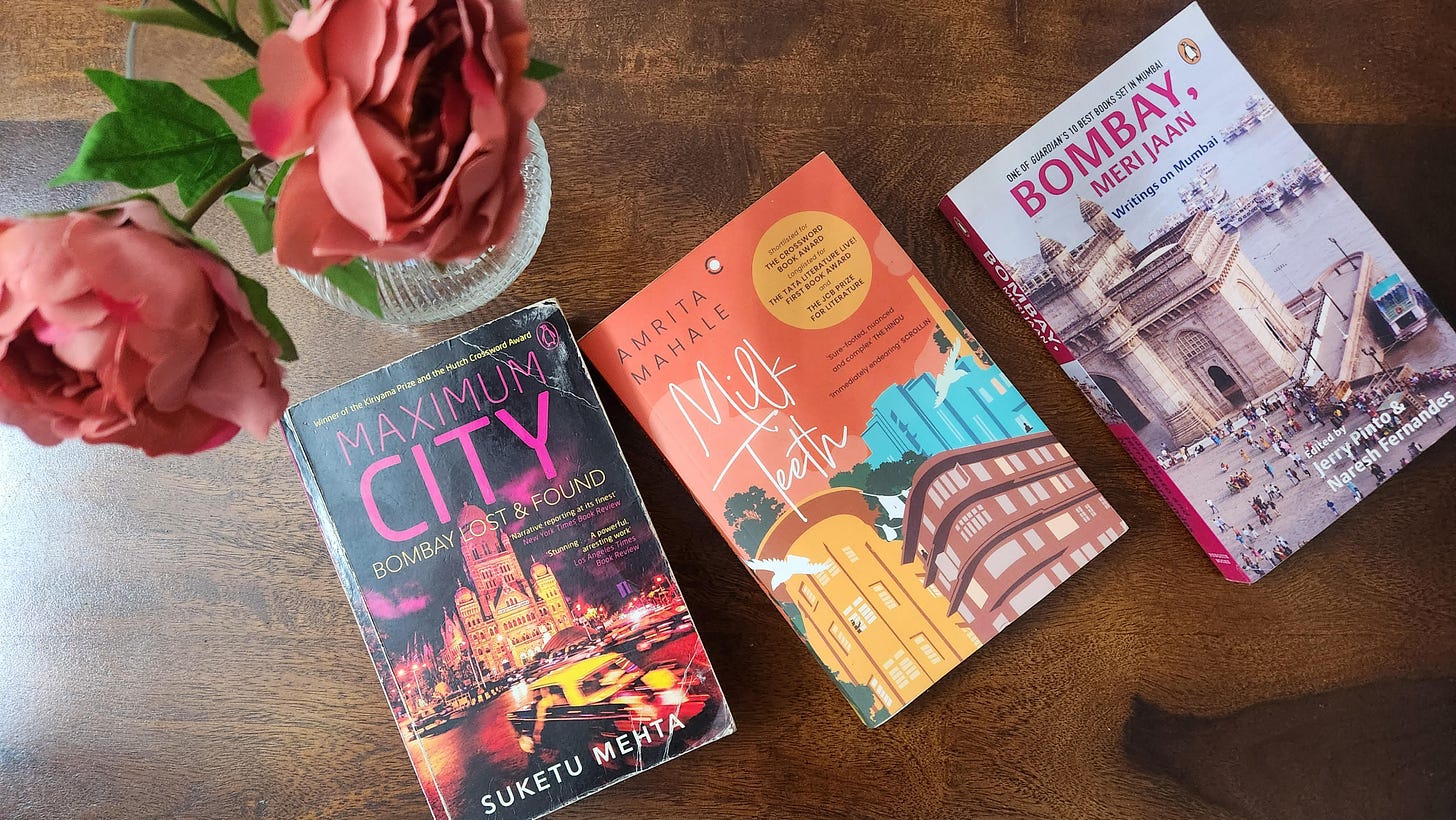

I pick up Maximum City by Suketu Mehta from a local bookshop as an encyclopaedic rendition of the city—why was the Mumbai Police considered second only to Scotland Yard? How did Kamathipura rise and why did the glamour fade? How did political power ebb and flow over the last few decades? I seek answers like I’m taking an entrance examination, an exam that determines if I allow myself to feel like a Mumbaikar.

When I read Amrita Mahale's Milk Teeth, it kindles in me an appreciation for Mumbai’s architecture, a fire not as bright as Kaiz’s, but enough to ensure the flaneuse in me can only walk looking up, always eyeing the statues and art deco buildings that line the city. Is this Indo-Sarcaenic? That, neo-Gothic? Coupled with my interest in history, I become my own Wikipedia—did you know that Benjamin Horniman of Horniman’s Circle broke the story of Jallianwala Bagh in London, and was arrested and deported for the same? I start looking for the Irani cafes Ira and Kaiz frequent in the book—Kaiz theorizes that they were the city’s first cosmopolitan space, ‘a beautiful chaos’—and drink the same chai, even though I, like Ira, would prefer coffee.

In Cuffe Parade one day, I chance upon Bombay, Meri Jaan, a collection of essays. The first essay by Pico Iyer opens at Sassoon dock, with the writer asking one to “go to Sassoon dock at break of day, and there before you are the two unchanging forces of Bombay, commerce and the sea, in jostling, clangorous, technicolour profusion”. I glance at my watch, it is quarter to six, I can’t make it at dawn but I can try to reach by dusk, and I walk over to the dock. I am the only woman around. Men are unloading cartons and boats with multicolour flags sit idle. Is the jostling and clamour subdued by the pandemic, or is it just the dusk? I don’t finish the essay, but I manage to live it.

I am by now knee deep in the waters of the city. The sand beneath my feet is soft, the grip of my toes solid. The stench around the fish markets doesn't bother me anymore, though that is primarily due to my weak nose. My taste buds are strong, however, and after reading Jane Borge’s Bombay Balchao, they crave a good prawn balchao. “Each time you prepare the balchao masala,” Ellena Gomes’ mother had told her in the book, “think of the person you want to feed it to…. If this person is somebody you love, you will be more careful, especially with your peppercorns and chillies. You don’t want to burn the tongue that has been kind to you.” No one I know can prepare balchao, but if I frequent the nearby Goan restaurant, sit and chat with the owners and the chefs, tempered with my recently acquired knowledge of Bombay Catholic history, the next time they make their pickle, will they think of me?

It is perhaps this naivety that brings me here, not an enviable trait in an unapologetic Mumbai. It is starry-eyed awe that makes me forget about the long hours of commute and the never-ending house hunts. There is a strong desire to belong, to fit in, to dissolve and I choose to lean on words to fight the unfamiliar, to ensure that the grip of my feet stays strong in the sand, even when the waters recede and my balance begins to give way. I hope that Mumbai accepts me, even as I scramble to learn to swim its waters and finish the pile of books on my shelf.

First of a three part series on life in a new city and how books helped me make sense of it. A version of this essay first appeared in Livemint (Oct ‘21).

Lovely, lovely piece. Opens up Mumbai through your eyes. Also makes me want to visit (I really should)

Really lovely, thought-provoking. I love Mumbai because I studied in South Bombay as an undergraduate. Now, I'm halfway across the world, living and working in a small town in France. Your musings on loneliness/isolation/solitude hit the spot beautifully for me.